The mailbag

Gerrymandering makes for interesting mail! Here are some excerpts from activists, a journalist, political scientist, and a few redistricters. ...

Senate: 48 Dem | 52 Rep (range: 47-52)

Control: R+2.9% from toss-up

Generic polling: Tie 0.0%

Control: Tie 0.0%

Harris: 265 EV (239-292, R+0.3% from toss-up)

Moneyball states: President NV PA NC

Click any tracker for analytics and data

(Welcome, New York Times readers!)

Thanks to commenters on this topic. Your feedback has shaped my thinking on this subject. I recall being skeptical that redistricting could have a major effect. As it turns out, the effects of partisan redistricting helped Republicans far more than I expected.

One reason for my skepticism is that the the effect was clustered tightly in a handful of swing states. My pre-election calculations did not look for state-specific effects (though they were still fairly accurate); it was only after the election that I developed the right statistical tools. All extreme partisan gerrymanders were done in states with GOP-controlled redistricting. Furthermore, they are swing states, putting them on a knife edge and making them places where gerrymandering could help eke out extra wins.

First, some links to previous essays. Then some answers to your questions.

October 4, 2012, “The Very Hungry Gerrymander“: I showed how partisan redistricting tilted the overall playing field for House elections. At the time, I estimated that the effect was equivalent to 13 seats (not too far off) and less than 2% of the popular vote (this was a serious underestimate).

December 30, 2012, “Gerrymanders (Part 1): Busting the ‘both-sides-do-it’ myth“: Here I figured out a general approach to identify specific offending states. The result: seven Republican-controlled gerrymanders, one Democratic-controlled.

January 2, 2012, “Gerrymanders (Part 2): How many voters were disenfranchised?“ Here I estimated the effective disenfranchisement of millions of Democratic voters, hundreds of thousands of GOP voters. There are different ways to do it, but the ratio is always similar.

>>>

Some questions with my replies:

It seems that an obvious solution is proportional representation: dividing up each state delegation by the percentage of the vote, and letting the political parties put up slates of candidates.

The multidistrict idea has logical appeal. However, it’s never been done in the US. People like being able to contact their own Congressman. In my view this proposal is a nonstarter. From the point of view of implementing actual change, it is impractical and a pipe dream to suggest it.

However, this does raise a logical issue, which is that clustering of voters is sometimes deemed to be good. The Voting Rights Act as implemented allows the implementation of things like “majority-minority” districts, where a small minority like blacks or Hispanics are packed together. In cases where a minority is far smaller than 50%, this is necessary.

The general principle is proportionality: If you’re 10-30% of the population (minority groups), packing is your only hope. If you’re 40-50% of the population, than packing can leave you out in the cold. I agree that an explicit proportional system addresses this problem. I just think it’s unavailable as a tool given our current legal framework. Of course, that framework could change someday.

Political scientists have claimed that the inherent clustering of Democrats in cities has led to a significant partisan imbalance that is structural (“districting”) rather than redistricting. Is that true?

This claim, made by political scientists, might have been true in past elections at a national level. But state-by-state, and this year nationwide thanks to partisan asymmetry, it is false. I note with emphasis that this essay by Stuart Rothenburg is incorrect.

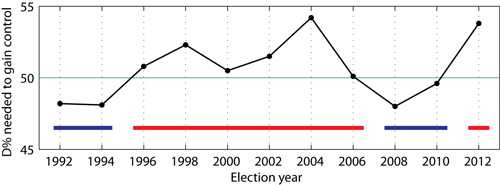

(1) Here is another demonstration. This graph shows what fraction of the two-party vote would have been needed for Democrats to control the House of Representatives.

The procedure was:

The colored horizontal line segments indicate which party was in control. Generally, the out-party needs a bit more than 50% of the two-party vote to gain control. This extra barrier is an advantage for the incumbent party. The 2012 value is unusually high – though interestingly, it’s matched by 2004.

I note that dealing with uncontested races is a challenge. For instance, the 2006 data point is distorted by the fact that there were 47 uncontested races won by Democrats (versus only 10 won by Republicans). Forty-seven is an unusually high number. With other definitions, this data point is more comparable to 1996-2004.

(2) Here is another demonstration. This is an example of the resampling analysis I used for the NYT piece.

Green points indicate resampling from all districts (minus at-large and gerrymandered states). Black points indicate resampling from the same districts, but furthermore removing high-density and urbanized states. As you can see, the green and black clouds are basically in line. The red circle is a the actual seat breakdown of seven strong GOP gerrymanders: PA, OH, MI, NC, VA, FL, and IN.

Two conclusions here: (1) urbanized states and all states behave similarly when resampled, and (2) the effect of partisan gerrymandering dwarfs whatever variations are present at a national level.

>>>

I’ll post a more questions as they arise.

Great piece in the Times today Dr. Wang. Your conclusion shocks me not. I’ve already seen other articles that show the parties gearing up for 2020 already.

On another subject, I recently met with Education Commissioner Christopher Cerf about teacher evaluation. The post is on my blog, which you can get to by clicking on my name.

It would be great if you could extend your analytical method to the affect on voting behavior of members elected through distorted redistricting. The political science point is that with competitive seats, candidates must appeal to a broader set of constituents and can campaign on ‘governing from the middle’ and accomplishing by compromise. With safe seats, the number exaggerated by redistricting, the competition comes not from the other party Instead, any competition comes instead from his/her own political party, therefore urging more orthodoxy on the candidate and disfavoring flexibility and compromise. This point seems to be illustrated by a legislative class of more conservative and less interested in compromise Republican House Members. While association does not necessarily mean causation, my instinct tells me that the two are connected. But this receives little mention and I don’t think it has been approached empirically.

Based on individual motivations, I would expect candidates to be more oriented toward factors that get them elected. If partisan majorities are larger, then they would cater to primary voters. If incumbents are protected, then they would stick with party leaders. In that last case, there is a chicken-and-egg problem.

There are claims among political scientists (which maybe you know about) that gerrymandering and polarization are unconnected. It would be worthwhile to dig into that literature and see how they arrived at that conclusion.

One obvious result of gerrymandering is exactly what Dr. Wang alludes to as House polarization. The result of gerrymandered districts is that while the GOP candidate becomes immunized to a challenge from the left, they become vulnerable to a challenge from the fringe right, being ‘primaried’ by the local tea party candidate.

Thus Boehner has an intractable caucus held in babylonian thrall to the teahadists.

The other looming doom of the GOP is the Benchpress Project and the democratization of information provided by the Web.

Daylight kills.

I have written a fictional trilogy in which the primary theme is five Constitutional amendments to bring this magnificent document into the 21st Century. They are listed on the first page of my website.

I am currently at work on a short non-fiction book to “Renew the Constitution” and while I have a Constitutional Law professor involved in the project, I would welcome your participation.

Please look at the Amendments and see if they make sense to you and align with your thinking.

If so, I would welcome your collaboration on the project.

I believe that whatever 300 million of us want, we can have. “We, the people…” are the three most powerful words in the English language.

Dixie Swanson

Congratulations on the NYT piece. Seems like it accomplishes everything you set out to do. Hopefully it will produce more fruitful dialogues going forward.

I do part ways with you somewhat re proportional representation. Just because something hasn’t been done much (the Illinois House used PR for roughly a century in 3-member districts) is not a good reason to disregard it so thoroughly. Even if it’s not “politically realistic”, keeping it alive in the ideosphere influences how we see other ideas & proposals–and that can be very important.

For one thing, the notion of “wasted votes” which you touch on, is actually a much bigger deal than your approach recognized. The number of votes “wasted” — meaning their votes don’t elect a representative — in any N-seat race is V*/(N+1)-1, where V=# of voters. When N=1, that’s 50%-1, because only 50%+1 are needed to elect, so all votes for the losing candidate are wasted, but so are all the extra votes that the winner didn’t need. When N=2, it’s 33 1/3%-1, and so on. The drop in wasted votes from N=3 to N=4 is just 5% of the total, so that CAN be regarded as an attractive cut-off point, when considering the trade-offs with having an identifiable local representative.

Second point: you write about “Voting Rights Act as implemented”. It should be noted that Lani Guinier was intensely concerned about the Voting Rights Act and the growing grap between original political intentions and how it was working out in practice. This concern is what lead her to her interest in proportional representation, and her scholarship in this area remains light-years beyond what most others are saying. The fact that she was mercilessly demonized without ever getting the chance to defend herself is a measure of how deeply pathological US political culture was even as early as 1993, but it definitely should not constrain us in trying to think our way beyond this deplorable state of affairs.

Anyway, while these are important points to keep in mind for the long run they in no way detract from my appreciation of the specific advances in clarifying the problems we face that your work here represents. So, again, congratulations. I look forward to what comes out of it next–both from you, and from the response of others.

Thank you for these thoughtful points.

I see what you mean about proportional representation. I agree that it needs to be kept alive. However, I don’t see that as the way to move the needle on representative government in the coming 10 years. So I do not advocate working on the more idealistic solution.

This is the same reasoning that leads me to encourage people, every chance I get, to contribute and work on races where the probability of a win is between 20 and 80%.

Sam, I totally agree about what’s practical. We need t0 be able to walk & chew gum at the same time: present a clear picture of what a more ideal system would be like as a supporting argument for more achievable improvement within the framework of existing accepted ideas. It’s foolish & self-destructive to always pit the perfect vs. the good, when the indisputable point is to get better, not worse.

Just sent a note to Sam, but will share the relevant part here.

It’s not true that we have always used one-seat districts.. In fact at-large House elections were common for the first 50 years in the US, and the 1842 law requiring one-seat districts came to prevent the unfairness of winner-take-all at-large just before the first writings explaining how to do proportional voting were done. The requirement has come and gone since — most recently re-imposed in 1967, leading Hawaii and New Mexico to have to adopt one-seat districts

Meanwhile, most local election are not elected in one-seat districts, and in the first half of the 20th century, more than half of state legislators were not elected in one-seat districts. Today, many states, including your state of NJ and mine of MD, don’t have one-seat districts for their house.

To be sure, winning proportional voting won’t be easy. But winning redistricting reform won’t either, especially when it doesn’t do what you and others claim it does — while fair voting actually will do what we claim it does.

So keep an open mind and check out our maps FairVoting.US.

Nice to read you on the printed page. I liked the block-map graphic as well, very professional looking.

Devil’s advocate question about the simulated districts: Republicans could claim that states like PA etc are “naturally” gerrymandered, because so many Dems jam themselves into two urban areas.

That’s just the way PA is constructed.

In this argument, taking “national average” districts, as your simulation does, isn’t fair because what does a district in Montanna or Wyoming have to do with the realities on the ground in PA?

Is there a set of algorithms/guidelines that could create fair (or at least unbiased) districts without taking things like voting preferences (or proxies like ethnicity or wealth) into account?

Urban areas: yes, that was the point of my last plot in this post. The short answer is that it’s not the problem because without the gerrymandering, the balance point for a takeover is usually quite close to 50% of the popular vote.

That argument seems not to be going away. I will have to tackle it head-on.

Just to chime in here, the PA delegation was split 11-10 in 1990s, sometimes Dems had the 11, sometimes Reps did. Has the political geography really changed that much in such a short period of time? Many citizens of PA thought not. The Supreme Court case Sam cites was brought against the GOP’s political gerrymander of PA after the 2000 census. The post-2010 districts were even more stacked against the Dems. I do not doubt that there’s been SOME increase in party polarization on the ground. But not nearly enough to make the rapid shift from away from an 11/10 split a geographical inevitability.

Regarding a partisan-free algorithm for creating unbiased districts: Couldn’t you simply say that the plan with the lowest district-perimeter-to-district-area ratio is the accepted one? This reduces the problem to a mathematical one–the politicians can leave the room, since no political considerations are taken into account.

I can assure you that drawing good districts is harder than that. However, it’s a useful criterion – one that most redistricters already use. The question is one of legal mechanisms to move outcomes in that direction.

To be clear, I was positing Republican responses to the analysis, not actual faults with the work. CA, with its huge spectrum of population density, manages to get it basically right. I suspect even in states like Montana, Democrats are clustered around the college towns.

Of course, another Republican rejoinder will be: It’s not our fault that Democrats only turn out for big ticket elections where a charismatic candidate is on the national ballot. Republicans turn out for the unglamorous state and local elections. You want a seat at the table when lines are being drawn, then show up.

I fear this sort of argument is harder to counter.

Amit, OFA is the counter strat. And it’s not going away, just morphing into Organizing for Action. Like ACORN without the liability of gov fundage. GOP is making a lot of noise about the tech gap but reproducing OFA’s election results isn’t possible for them. Conservative base turnout is already pretty much maxed because of asymmetrical enthusiasm in red phenotypes.

Conservatives have two intractable problems that I see no strategic remedy for– 1) shrinking white share of the electorate and 2) the democratization of information provided by social media and the Internet. Vote suppression and gerrymandering are tactical strikes on the strategic problems.

We are going to see internecine warfare in the GOP for the next two years while the leadership tries to integrate and educate the base. Meanwhile OFA never sleeps.

Expect us.

Here is a thought experiment. Imagine how politics would be different if we had state Congressional delegations that were winner-take-all. You would still have districts and primaries would be on a district basis. Everyone would still have “their” representative. But the party that got the most votes statewide would get all the seats.

This is an improvement? It seems to me that it might things worse, not better. Primary voters would have little incentive to choose a moderate in the interest of electability, since the views of any one member of the party’s statewide slate would be diluted by the other candidates on the slate. Primary voters in Senate races often choose an extremist (Akin, Murdock), and this tendency would be even more pronounced in a system where an extremist would be only one member of a statewide slate.

Also, there may well be constituencies that want “their” congressperson elected, and elected comfortably. Even if he or she is in the minority in the House.

For instance, Pallone in NJ6 is big on issues affecting Indian-Americans. I’ve seen his portrait in Indian restaurants around here. He is part of the India caucus, and got an award from the Indian govt.

And Pallone wins lopsided elections (I don’t know if gerrymandering is involved here, but still). For a lot of his constituents, it’s probably more important to keep someone in office they have built up a long-term relationship. Who wants to break in a new set of aides every election?

Also, lopsided elections mean your congressperson isn’t hitting you up for money as much.

My thought experiment was not meant as a suggested course of action. I want to draw attention to the fact that changing the rules changes the players’ strategies. You cannot just assume that the way to evaluate a change in the electoral rules is to look at what the results of the last election would have been if you retroactively apply the rules.

Election processes are dynamic and unintended consequences are a given.

Dr. Wang,

congrats on the piece in the NYT.

First of all, congratulations on the NYT piece. It was a wake-up call the country needs.

But there are deleterious effects of gerrymandering beyond just illicit representation. I wrote about this in July of 2009 here:

http://www.futuresearch.com/futureblog/2009/07/15/why-american-politics-is-dysfunctional-–-and-dangerous/#more-231

Please, keep up the fight. It’s important!

Thanks,

Richard

I enjoyed reading your article and diagrams in the New York Times. It was understandable by one “statistically challenged.” Keep on slaying gerrymandering with your verbal sword.

Following the development of this article over the past weeks with the assistance of all the helpful contributors to this blog was fascinating.

Pardon the OT but you guys HAVE to see this.

The genius of Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

Like our discussions of Stewart and Colbert.

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Nassim-Nicholas-Taleb/13012333374

I’ve often wondered whether the answer is a larger house of representatives. The size of the House has stayed constant for a century while the population has tripled. Making districts smaller makes them harder to gerrymander, makes it easier for people to know their representative, makes elections for House districts less expensive, and dilutes all of the lobbying money floating around D.C.

Short question on the scatter plot above. The green dots are the resampled states, and black dots is the same dataset but with highly urbanized states removed.

Then why do the black dots lie at higher D percentage than the green dots? Usually dense&urban = more dem, no?

Also, what is best fit to the cloud? Looks like it goes through (50,50) but isn’t quite diagonal. 45% of the vote gets you 35% of the seats, even without gerrymandering.

Also, red circle at (50,35) is combination of PA, OH, MI, NC, VA, FL, IN? What are coordinates of there states individually? If I take the scatter of the dots as ~1sigma, then the red circle is about 2 sigma off. How far from the cloud are the individual states?

I am not a mathematician, but it seems to me that there must be a purely objective, discretionless way to create congressional districts.

For example: Start at the northernmost point of the state, move as far due east from there as you can go within the state (Point A), and then take the point due southwest from there (Point C) such that Point A, Point C, the point as far north from Point C as you can go within the state (Point B), and the point as far east from Point C as you can go within the state (Point D) bound an area with the required population. Then repeat, treating the first drawn district as being outside of the state.

Depending on the geography of the state, districts drawn by a method like this may not be ideally compact, they may divide communities, they may not respect topographical and they may not maximize the voting clout of any particular group, but they would have the advantage of leaving the linedrawing to the discretion of no one. Every 10 years, the linedrawing could start from a different corner of the state.

If the method is completely objective like this, then perhaps a sufficient number of states would be willing to pass a constitutional amendment to require it. Or perhaps the courts could be convinced to require it, under the principle of one person-one vote.

People with similar concerns may want to be in the same collective. For instance, a person on the Jersey shore might have more issues in common with someone several dozen miles down the shore than with someone just a couple of miles inland.

Arbitrary borders have a sad history. Look up Radcliffe and Durand lines.

I’m curious about the slight D lean to Texas. I recall (and wiki confirms for what its worth) that DeLay organized a redistricting in 03 that resulted in the loss of multiple D seats.

Do I have this story wrong? Or are the redistricted and gerrymandered seats fragile?

It seems to me that if you pack districts in a system in which turnout is highly variable, you risk making the seats you are trying to protect fragile. If that is true, you either need to redistrict with each election cycle or risk big swings in your delegate composition.

Anyone understand whats happening in Texas?

Do you have enough statistics on women’s propensity to cross party lines to determine whether a democratic strategy on focusing on women’s issues on gerrymandered districts has a realistic chance of winning enough districts to gain control of congress?

I want to work with a Virginia or national organization that is taking meaningful ACTION to stop gerrymandering. (I’ve no statement to make. I’m from your grandmother’s ‘just do it’ generation.)

The argument in favor of single member districts runs something like this. In a pure PR setup, the party nominates whatever hacks it wants, and people vote for the party. The representatives’ loyalty is to the party and not to the voters of their district. I have to throw the whole party out if a representative is a bum. I am from Illinois. Chicago will always vote Democratic. Outside the six county Chicagoland area, they will always vote Republican. This means the top 25% Republicans and top ~40% Democrats will always get elected until they get convicted of breaking the law. There is no accountability. It’s bad enough when Michael Madigan can control large portions of the state’s priorities, just because he is house speaker. We could only demote him by electing a Republican majority in the state House. Let’s not make it easier to elect lots more of them.