Herding, or judgment?

After all the canvassing, donation, and activism, tonight now we observe. Later this afternoon I will publish the Princeton Election Consortium biennial Geek’s Guide to the election. It will detail what I will be watching.

This is also an open thread – please chime in. I may host a Zoom call tonight as well – stay tuned.

Reweighting can be mistaken for herding

There’s a lot of talk about how pollsters are watching each other, and coming up with results that don’t get too far out of line with the average. This is called herding.

In my view herding is somewhat overblown, and not to be confused with expert judgment. It is hard to tell the difference, but I would caution against impugning the craft of how one generates a good survey sample.

Pollsters are faced with the problem of identifying who will vote, and normalizing their sample to match. If some demographic of people is disproportionately likely to answer a survey, more often than they would vote, then pollsters have to weight those responses appropriately. This is a matter of judgment.

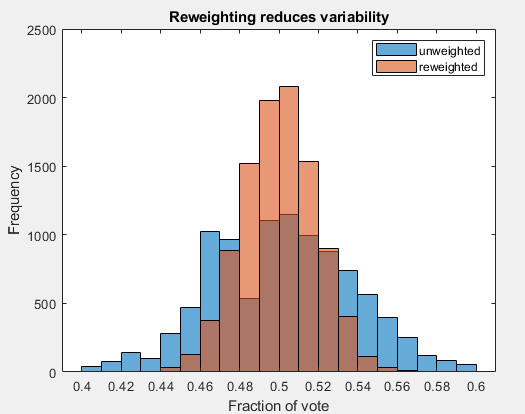

As it turns out, re-weighting reduces variability. Here is an example.

Imagine 3 groups of voters, distributed as 45% Democratic-leaning, 10% independent, and Republican (45%). They vote for the D candidate with probability 0.9, 0.5, and 0.1 respectively.

Below in blue is the raw result of 10,000 simulations of samples from this population (my MATLAB script is here). The results are pretty spread out.

In red are the same results, reweighting the sample with prior known proportions of the voter population. Reweighting narrows the apparent result. Pollsters reweight by more variables, and these various weightings (sometimes it’s called raking) will narrow the distribution further. This is just what pollsters do routinely.

The judgment comes from knowing what weights to use. Every pollster has their own set of weights that they use. Poll aggregation collects the crowd wisdom of these pollsters. In the aggregate, they will still be off – that is called systematic error.

How much will the systematic error be this year? In 2016, it was about 1.5 points, leading to a surprise Trump win. It would not be crazy to imagine an error that large in 2024. But in which direction, I don’t know.

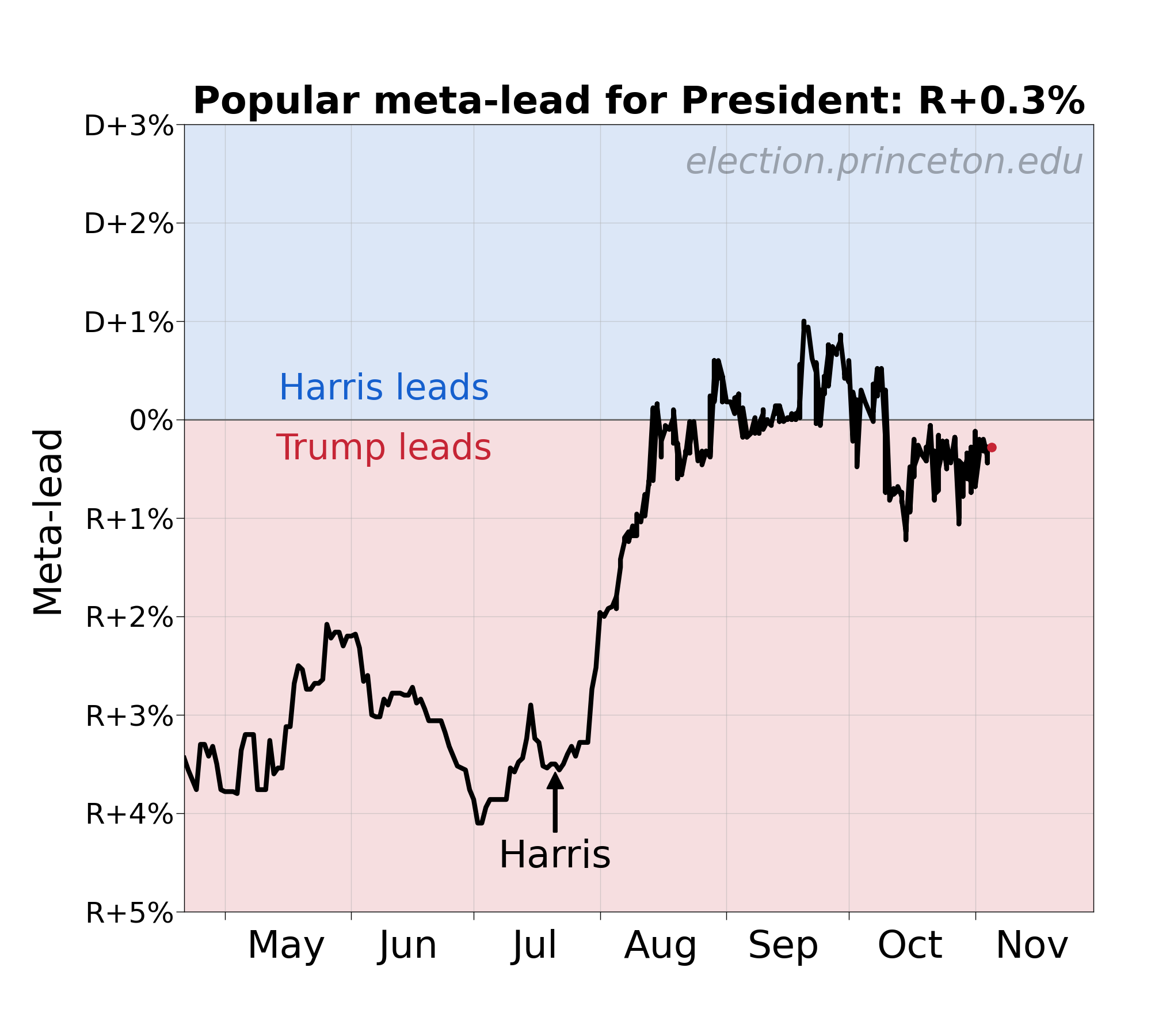

The one thing we can say is that this error is much larger than the virtual margin of the presidential race, where that margin is defined in terms of how far the race is from a perfect electoral tie. I calculate this “meta-margin” as Trump +0.3%. That’s much smaller than the error. This has two implications:

- We don’t know who’s going to win based on polls alone.

- The final outcome is likely to be less close in one direction or the other.

Later this afternoon I will give evidence for why I believe the error will end up favoring Kamala Harris.

I’ve heard a couple of interviews with Anne Selzer and discussions of her polling in an extremely ethnically (race isn’t a biological thing) homogenous state where many types of weighting isn’t used or possibly needed. The discussions comparing her polling to others where she does not weight or model on prior contests makes me think it is near impossible to accurately model with a sui generis like Trump.

Quick note: Typo about Trump in 2026 – pretty sure you meant 2016. (Hi Sam!)

Thank you, Jeff!

I think one feature of the meta-margin has been its remarkable stability and thus its ability to reveal truly opinion-moving events during the election cycle. Is the meta-margin line less stable this year? Are the movements less tied to obvious factors in the campaigns (e.g. “convention bounce” or big piece of news)? Is it less precise? If so, what does that instability mean?

I get that weighting can reduce variability below naive sampling error*, but the example raises my eyebrows. The weights are supposed to be based on “prior known proportions of the voter population” but I thought that weighting on party ID was already a rejected method? (Specifically, because it removes the actual unknown variability in turnout and party ID changes between elections.) I seem to remember some unsavory characters in previous cycles even attempted to, uh, adjust polls that way, and it ultimately proved to be misinformative, to their and their followers’ literal peril.

But more to the point of discourse this year, the argument is that weighting by 2020 vote as recalled by the voter has the same weaknesses due to previously demonstrated inaccuracies in voters’ memory – unless the weighting scheme is anticipating and weighting after such effects, perhaps?

* For stronger intuition for other readers, I offer this contrived example: You have a bag of 4 double-headed coins, one unfair coin, and 4 double-tailed coins. You may only draw a (uniformly) random coin, look at it, and flip it once, before returning it to the bag. How do you most efficiently estimate the overall chances of heads and tails?

If you just tally the flip results, there’s a lot of “useless” variability from drawing the double-headed and -tailed coins – the only new information is in the unfair coin’s tosses, and you might as well just use the information as given for the the double-headed and -tailed coins. And this pans out: your estimate converges faster by observing what type of coin you drew and isolating an estimate of the unfair coin.

I’m from Iowa Folks,, this ain’t 2020 for sure here…or 2016…the Selzer poll says it all..Expect the unexpected….It may be 2-3 days before we know or could be early AM..Who knows…..